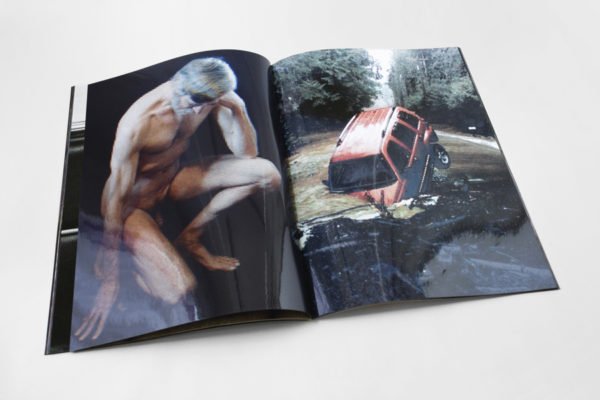

Nude Kneeling, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann

Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published on our previous platform, In the In-Between: Journal of Digital Imaging Artists, and the formatting has not been optimized for the new website.

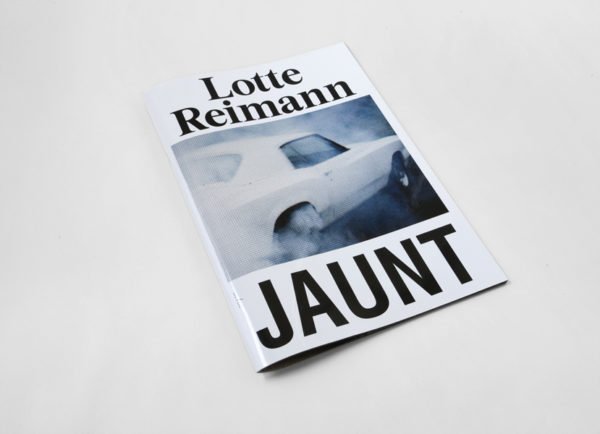

German artist Lotte Reimann’s project Jaunt is a series of web-appropriated imagery that has been edited to function as erotica that blurs the lines of documentary and fantasy. The bulk of the images she uses for this work were sourced froma single group of pictures uploaded online by an annonymous couple who created and shared portraits and self-portraits of themselves engaging in nude poses and sexual behaviors. Combining this imagery with pictures of cars crashing, racing and burning out, Reimann creates a fetishistic narrative that embraces a genre of literature that does not often cross over into photographic dialogue.

______________________________________________

Gregory Eddi Jones: First off Lotte, can you offer us insight into your background as a photographic artist, and talk about some of the influences that have helped to shape your practice?

Lotte Reimann: I got my first camera when I was 8 and have been intrigued by photography ever since. That being said, I’ve never been the stereotype photographer with a camera around my neck. Nevertheless I found myself at an applied photography school with a documentary approach, probably because my family has a rather practically working background. After somehow failing at regular commissions, because I was unable to let go of my own ideas, I decided to transfer to art school. I think until now those teachings had the greatest impact on my work. First I “learned” what to look at and then how to do that from my own perspective.

In general I don’t see myself as a photographer but rather as a storyteller, working with found amateur material, illuminating it from my personal perspective. I blend authenticity with fiction, document with prose and autobiography with a third person narrator.

Nude on Passenger Seat, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

Half Nude on Car Sputtering, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

GJ: Web technologies have given way for a relatively new species of artists to emerge, those that function as editors who recycle images rather than produce them, and who re-author images to shape their meanings with new voices. This ocean of images we have access to online can be considered as raw material for new works to be built from. Talk more about your drive to work in this fashion, to shape as opposed to make. What do you feel is the key to successful appropriative gestures?

LR: Appropriation has a long tradition in the arts. This new species you’re talking of is, I guess, the artistic assimilation of a relatively new media (the digital image on the internet). But it somehow follows the same “rules” as the older media (analog images).

However, for me working with found material did not happen overnight, but was a slow process. Starting from a documentary approach, my autobiographic series Guffaw from 2011 was the first project containing some images I did not photograph myself: self-portraits of my mother that I commissioned. I guess this was my key to working with “found” material. Since then I slowly shifted from actual self-portrayal to observing how other people present themselves through imagery and thanks to the internet I can do this almost “live” – with brand new images opposed to e.g. images from old family albums found in thrift stores.

But I don’t limit my work to found material. For example in the Reflections series from 2014 I included images that I shot myself. I uploaded those to ebay as a bait to get in touch with reflectoporn fetishists. Basically, I think it doesn’t matter if you “shape” or make images yourself. It is about what those images tell in the context you present them.

As I indicated before, I am not interested in giving a supposedly objective or documentary view on things but in being clear about the subjectiveness of photography and therefore I show things from an obviously personal, sometimes even fictional, perspective.

I see this as a key to successful appropriation: showing your own unique view on existing things. Maybe your own view is personal / fictional, like mine, maybe it is rather general / re-ordered, like the work of Hans-Peter Feldmann or Peter Piller. It’s all about meaningful re-contextualization, I suppose.

Burnout at Blue Hour, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

GJ: For your work in Jaunt, you blended together a group of images that express themes of erotica and fetishism, using amateur pornography and pictures of cars burning rubber, kicking up dust. Can you give us an introduction to this work, and talk about how you found these images and why you decided to work with them?

LR: Jaunt is based on a collection of nude self-portraits of an American amateur photographer couple I found on a picture sharing site comparable to flickr. What instantly fascinated me were the images in which he poses naked inside a car. On top of the rare theme “the male nude”, he has quite a good eye for lightning and composition, but with this amateuristic imperfection to it – which is crucial for my work for different reasons we might come back later to.

Initially, I wanted to truthfully recount the couple’s story by means of a straight selection, but I quickly realized that the story I pictured exceeded their archive. So whenever I sensed a gap in my storyline I added an image from a random other source on the internet.

In the end I am telling my own fictional story, based on their images and inspired by JG Ballard’s book, Crash (Jonathan Cape, 1973). This novel is about a man discovering his sexual arousal is linked to cars crashing, and it has long been an inspiration to my work but especially to this project…

When I came across Mr. and Mrs. T.’s archive I’ve been strolling the internet for nude pictures with a rather unsharp idea in mind. Sometime before I had realized that I have an unsatisfied longing for erotic photography. Why unsatisfied? Because I couldn’t find my own penchants within those floods of pornography? Or because it’s always females looked at from a male perspective?

Well, I guess this longing was the actual reason for me to become entangled in the couple’s archive. A male looked at from a male perspective, a female looked at from a female perspective (it’s all self-portraits) and me observing them; twisting my own fantasies and penchants into the final narration.

All images in the book are re-photographed from my computer screens and thereby changed extensively. I zoom in, I photoshop, I paint and erase; basically I do what classic photographers do with their own raw material – maybe even a bit more…

Half Nude on Back Seat, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

Burnout Take Off, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

GJ: There are strong polarizations present in this project that you’ve used to establish a taut conceptual tension. You take the position as a voyeur in compiling this work, but it’s a viewpoint this couple has invited by publicly sharing these images. There is a degree of vulnerability assumed by the nude bodies being gazed, yet there’s aggression and violence inferred in burning rubber and crashed cars. Even the title, Jaunt, implies a sense of fun and light-heartedness, but behind the veil there seems to be a real sense of psychological intrigue happening. Is this analysis in line with the longing you said you felt when deciding to work with these images? I’m interested to hear more, because female eroticism seems to be a particularly rare photographic genre.

LR: Hey, great. I didn’t yet realize all those contrasting juxtapositions myself. But you’re very right, in general ambiguity and clashes are important aspects of my works. For me it’s always about wondering, contrasting, asking. It is not about presenting answers, but addressing questions visually / legibly.

Is there something like female or male eroticism at all? Or is it rather an interpersonal phenomenon, regardless of sex and gender?

I am extremely fascinated by how contrasts not only depend on each other but also belong together psychologically. For example sad / painful and funny, like Buster Keaton, or adrenaline, which actually makes you feel alive but is often released by a threat of harm.

When I was in my early twenties, my brother and me were, independently of each other, having really bad times. One drunk evening we decided to go punch each other’s face – just for the sake of doing it, not because we were fighting. And paradoxically, although it did hurt physically, it made us feel a lot better emotionally.

Skid Marks, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

GJ: You mentioned the amateurism of the images you use is crucial to your work, why is that?

LR: My work is a lot about self-presentation and individuation in the digital age. By working with amateur material I try to relate to visual everyday life.

In the arts self-portrayal is something very old. Think about the first self-portraits, of e.g. Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban from 1433. While working with self-portraits from artists would primarily refer to art itself, working with the “selfie” (which seems to affect the whole society right now) is rather pointing at cultural developments.

Almost all my images (also those that are not self-portraits) stem from personal amateur albums shared publicly on the internet. It is this flood of pictures, with which we try to show the world who we are, that interests me. This still growing trend of individualism.

Nude Sitting, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

GJ: Jaunt was published as an artists’ book by Art Paper Editions earlier this year. Can you talk about the making of the book, how it came about, and the challenges you faced in finding its final form?

LR: The project was initially planned and compiled as a book. So at first there were no problems as in transformation from space into book, which I experienced earlier with other works.

I started editing the story in a layout-application from the scratch and determined certain rules in the very beginning. E.g. I wanted the book to be simple: one image per page, full-bleed, no tilting, etc. to accomplish an easy flipping through the book and the feeling of a narrative sequence (flip-book). But I also wanted the images to be as big as possible in an ordinary book format, to come “close” to the screen.

Basically, when Jurgen Maelfeydt from Art Paper Editions stepped in he gave his fresh look upon the project and came up with some very good ideas for production. He re-edited the sequence (which was great because I got too obsessed with details that didn’t matter in the end), and he designed the cover, and chose for the conceptually fantastic glossy finish of the paper.

In retrospective the whole process felt quite smooth. But it did take its time, of course.

GJ: Thanks a lot for your insights Lotte. What are you looking forward to over the next year, photographically or otherwise?

LR: At the moment I am preparing my first solo show at the Berlin-based gallery Leslie in March, which I’m quite excited about. We will show Jaunt among other works.

And I’m hoping to find a bigger atelier soon, to be able to carefully develop large-scale installations and focus on images in space again. I do love making books, but I also have the feeling I have put all my energy into that over the past years. So I feel it’s time for a change.

It doesn’t mean I won’t make any more books. I just want to try out other things, too.

So my new, yet unfinished, series “Drapery Studies” already started to become slightly more 3 dimensional. The images will be treated and finished differently, according to their type; framed, mounted on wood or glued directly to the wall. And there will be a table piece in it, too.

Thank you too, Greg!

Accelerator, from the series Jaunt, 2014. © Lotte Reimann.

_____________________

Bio:

___________________________

Stay connected with In the In-Between