Gregory Jones: First off Ben, talk about when you developed your initial interests in photography, and who were among your earliest influences.

Ben Alper: I inherited my initial interest in photography from my grandfather, who was an avid “Sunday Photographer”. He never did it professionally, but he voraciously photographed family trips, domestic rites of passage, and pretty much anything else he could. I was lucky enough to be able to go on some of these trips – mostly to the National Parks out west – and was always given a camera of my own to use. The one I remember most vividly was a bright yellow point and shoot with a small built in flash. It was completely waterproof and fit in my pocket. I would carry it around and make photographs of anything and everything. In hindsight, I think I was somewhat mesmerized by the camera. I was mostly interested in it as a means of collection or possession. I had always been a collector, but photography afforded collection of a different kind. I was also aware, even at that young age, that the camera, particularly in concert with the flash, transformed what it saw. Years later I heard Garry Winogrand’s quote: “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed”. I think on some subconscious level that is what I was doing all those years ago.

_____________________________________

GJ: The images from your series Background Noise serve as a direct commentary on the effect of digitization on what’s now considered as an antiquated physical form of the family photograph. Tell us about the process of making these pictures. Are they from your own family’s collection?

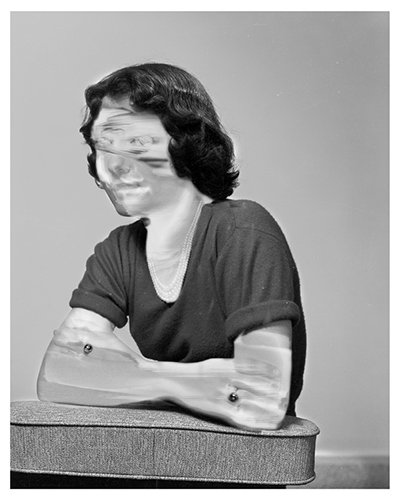

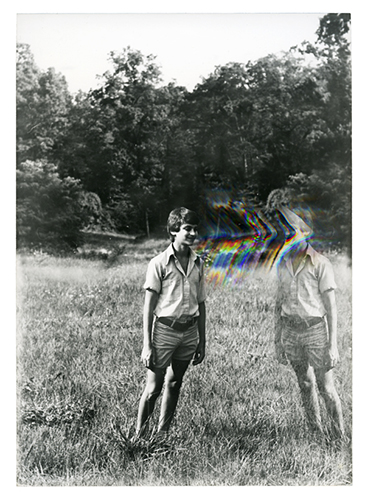

BA: The Background Noise work arose entirely out of chance and accident. I was scanning a negative, and somewhere along the way the file corrupted. The resulting image exhibited traces of its source, but was largely ruptured, an example of the kind of schism that permeates the digitization process. I was drawn to the mishap from an aesthetic standpoint, but even more so it underpinned an anxiety that I felt about the precariousness of digital media’s role in archiving and recalling personal and culture histories.

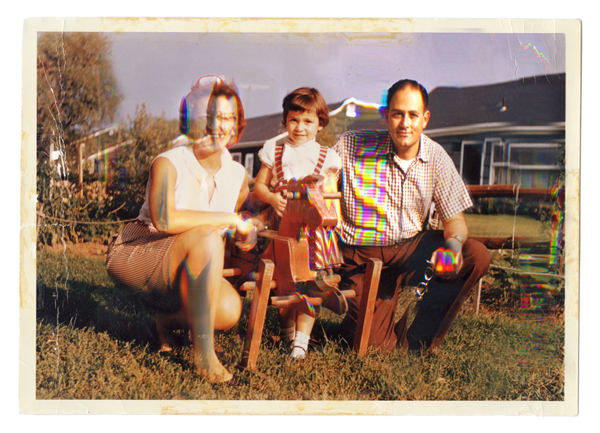

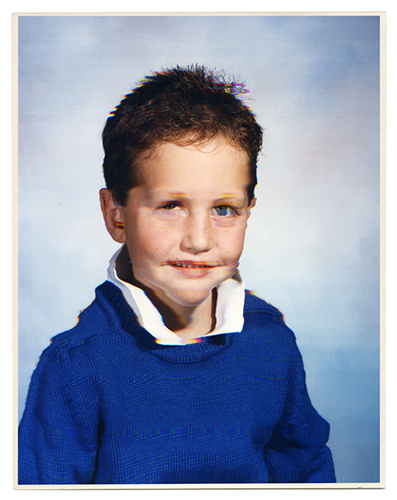

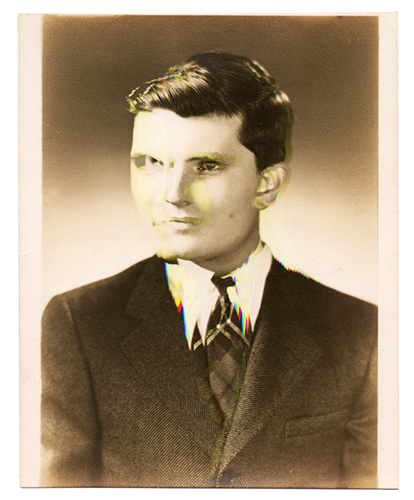

So, I began to make durational scans of vernacular photographs on a flatbed scanner. The process felt more akin to painting than it did to photography, as each gesture was entirely unique. Each piece reacted so differently to the action, which was fascinating. The length of time, the amount of movement, and the content of the image all factored in heavily to what the distortion ultimately looked like. I then made a straight scan of the same print and began the process of compositing small fractions of the disfigured image on top of the original. It was important to me that the digital interference created by the scanner didn’t entirely overwhelm the existent image. I wanted there to be a tension between the two – an uneasy marriage of outmoded and contemporary archiving practices.

Some of the photographs were culled from my own family’s collection, and some were anonymously found in junk stores and thrift shops. I was less interested in Background Noise being a project that focused exclusively on my own familial history. Rather, I hoped to address broader cultural issues surrounding the archiving, ordering, and recalling of personal photographic histories in a digital age. For that reason, I selected images that felt more iconic, more apart of an American vernacular lexicon of sorts.

____________________________

GJ: In reading these images, and the skewed RGB interventions found within, I’m still able to build my own stories about the history each image depicts. It seems that you don’t push the original imagery past the point of dissonance, where the original meaning becomes fully lost. My question is: why not?

BA: Like I started to mention above, I wanted to create a visual tension between the digital interference and the content of the original image. I experimented with varying degrees of distortion, however, I decided that I wanted to achieve more of a balance between the two. So, minor fissures, or partial breakdowns, pervade the image plane instead of total disintegration. When I began thinking about this work in 2010, the transition to digital archiving and preservation was certainly well under way. That may be a bit of an understatement, but simultaneously there existed, and still does, a generational tendency toward systematizing personal histories in physical photo albums. At the risk of generalization, this practice still holds true for many people of my parents and grandparents generation. As a result, I didn’t want the narrative leanings of the source images to be completely lost and inaccessible. I wanted the images to feel transitional, situated between the oppositional poles of analog and digital archiving. When our generation is the age that our grandparents are now, the takeover will be predominately complete. We will be the only ones to remember what a physical family album looked like, how the experience differs from viewing a set of images in iPhoto, and how intimate that experience can be.

________________________

GJ: Our generation, the millennial generation, is the one that history will recall as having matured hand-in-hand with the digital revolution. We recall the days of phones with cords, we remember what it was like before the internet. I don’t think it’s quite a stretch to offer an overarching generalization that nearly all our initial experiences with photography came from the family album and the family camera. In fact, nearly all the artists I’ve interviewed share that point of experience. Images viewed on a screen can, in a way, be considered less sacred than those images we can hold in our hands. When we feel the weight of a family album, and brush the dust of its cover, there’s a real intimacy to that experience. Is this something you miss?

BA: Yes, definitely. I struggle to connect with virtual images. My early obsession with my family’s albums was very much related to the physicality of the experience. I loved turning the pages and reading the captions. I often tried to piece together narratives of places and events that occurred before I was born. There was also a sensory component that I enjoyed – the old albums always smelled kind of musty, the photographs were often yellowing, and they were just satisfying to leaf through.

Having lost entire hard drives full of work (almost 7 years worth in one crash) I definitely have a slight anxiety about the stability of the digital images. It’s so easy to have all of your family/personal photographs eradicated in an instant. It’s definitely a paradigm shift, that’s for sure.

_____________________________

GJ: Doing the math, the family photograph is probably the most widely made type of picture in the world. It’s daunting now, with mobile imaging, how many billions of images were made, even just this week, which function to compliment (or create? or replace?) personal memory. Additionally, I’ve found that old family photographs are among the most popular forms of visual information when it comes to exploring digital appropriation and re-interpretation. There seems to be a strong desire to explore the form in new ways, not only to explore new visual methodologies but in a way to pay homage to a rapidly changing genre. What does it mean to you to be exploring this family picture genre, which has long ago, in my view, gained the acceptance as photography’s most basic cultural function?

BA: I’ve collected vernacular photographs for some time, but I didn’t start incorporating them into my own work until much later. When I first moved to New York, I worked for a private art dealer. He had me do all kinds of different things, but one project I worked on for a while was digitizing the entirety of his family’s photo history. It was somewhat tedious, but while scanning a print one day the file corrupted in the process and left the image distorted almost beyond recognition. It retained certain characteristics of the original, but it was largely permeated by digital interference.

For me, using vernacular photographs, particularly those that exist as physical prints, is a way to raise questions about the shifting manner in which we archive and recall photographic histories today. My interest is not a particularly nostalgic one, although in some ways you can’t escape that dimension. My interest lies more in digitally intervening in the source imagery as a way of complicating or altering the meaning of the photograph, and underpinning the precariousness of digitization more generally. Utilizing family photographs from the mid-to-late 20th century seemed appropriate because they were the generation of images that most closely preceded the onset of the digital image as a ubiquitous photographic form.

I’ve moved away from this kind of work in the past few years, although I do still collect vernacular photography somewhat avidly.

____________________________

GJ: Nothing has caused such a dramatic shift in production and consumption of “memory pictures” as the pairing of social media and mobile imaging technology. The Oxford Dictionary has dubbed the term, “selfie” as the word of the year, and seemingly right before our eyes, the entire 1st world has undergone an unprecedented paradigm shift in regards to how it is experienced by us through the rapid rate of information exchange. Do you embrace these changes? Fear them? Do you have any predictions based on what you’ve witnessed over the last ten years on the changes that will occur over the next ten?

BA: This is a really good question, and one that I’ve thought about a lot. It’s hard to predict what the image landscape will look like in ten years, although I imagine it will continue to proliferate for some time. It seems likely that the ever-increasing rate of information dissemination and consumption will simply be more normalized ten years from now, more taken as a matter of course.

To be honest, it feels at times entirely oppressive and inescapable. I often crave to disconnect, but at this point, you almost have to make a concerted effort to do so. I have accepted the changes, but I can’t really say I’ve embraced them. I also wouldn’t say that I fear them either, but I am distrustful of them. Social networking platforms and online personas have greatly diminished the amount we actual engage with one another in real time and space. In this way, I do think the technological developments of the last 20 years have greatly isolated and polarized people from one another. In other ways, these same developments have brought many people together. So, it’s an endlessly complicated and multifaceted dynamic.

________________________________

GJ: Its worth mentioning that much of your work beyond Background Noise deals with issues of memory and archiving; you even began a Tumblr site, the Archival Impulse, to explore these issues at greater depth . Talk about the role of the image archive. Is it changing in this environment of over-saturation?

BA: Yes, I think image archives have been changing for some time. The emergence of the internet compelled governmental bureaus, institutions, museums, and libraries to begin the long task of digitizing their overwhelmingly extensive archives. And constituent with this undertaking was the materialization of new issues surrounding digital conservancy. So, in addition to the concerns regarding the physical object or document, these institutions now had to think about the digital file as an object unto itself – one that was inherently precarious and prone to deterioration.

I think what’s really changed though is the appearance of accessibility to archives in the digital age. Many people have historically perceived archives as authoritative, opaque, and unavailable. However, with many archives now available in a virtual form, there is an assumption of transparency. Again though, this may only be an appearance. The really exciting thing though is when people construct and make available their own archives for an online audience. My initial intention with The Archival Impulse was simply to share my vernacular photography collection with like-minded enthusiasts. Yet, as the collection grew, I began to see it as a project that sort of undermined the authority of a traditional archive – the images are entirely decontextualized, they do not adhere to strict forms of classification, and they span time and space quite dramatically.

Ultimately, I like that there are DIY archives of all kinds on the internet that challenge or erode ideas surrounding what an archive is, or should be. It’s one of the egalitarian aspects of the internet that I think has actually been a positive thing.

________________________________

GJ: In a recent interview you did with Zach Nader for Lavalette, you spoke about how digitization has impacted the many functions of the photographic image. To quote you: “…I do believe that photographs have lost some of their power and ability to act as memory objects. There are simply too many images to contend with.”

I agree that it’s difficult to discern such strong meaning from a single image when so many competing and contradictory ideas are so easily accessible. Its seems to me that this issue is occurring through a type of decentralization of image publishing and sharing. The rise of platforms for photography on the internet, this one included but social media in particular, has significantly contributed to the saturation of images you hark to, but I feel that although the power of a single image may now be less impactful, photography as a whole has been elevated towards even greater importance. Do you have thoughts on this argument? Can’t this sentiment also be applied to other media, like television or music?

BA: Yes, I think it is certainly applicable to television and music. Every form of expressive media has exploded somewhat exponentially. However, just to clarify, I still think photographs can be incredibly powerful, but it’s just that my ability to process and internalize them has been dulled. I’m speaking from a personal place and not making any generalizations about how other people navigate the oceans of images they encounter everyday.

Social media platforms have certainly contributed to the glut of images globally, but they have also been elemental in creating lines of connection, collaboration, and the exchange of ideas between people all over the world. They have also been important in revolutionary efforts in certain places in the Middle East, so it’s hard to deny their cultural value in specific instances. In other ways though, they are invasive and somewhat predatory, so it’s always a trade off.

I still fundamentally believe that photographs are vital, compelling, and deeply meaningful. It’s just that we live in a time of extensive over-saturation, consumption, and waste – not just of images, but of so many things. I think it’s really about finding your own conscientious ways of adjusting to the cultural conditions of the day. In the end, the amount I allow the ceaselessness of digital information to inundate me, is still largely my decision.

__________________________

GJ: Parting thoughts?

BA: Thank you for this opportunity – and for asking thoughtful and engaging questions!

___________________________

Bio:

Ben Alper is an artist based in North Carolina. He received a BFA in photography from the Massachusetts College of Art & Design in Boston and an MFA in Studio Art from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Alper’s work has been shown widely, including exhibitions at the NADA Art Fair in Miami, the Luminary Center for the Arts in St. Louis, Le Dictateur Gallery in Milan, Italy, Meulensteen and Michael Matthews galleries in New York and at Johalla Projects and Schneider Gallery in Chicago. Additionally, his work has been published in The Collector’s Guide to New Art Photography Vol. 2, Conveyor Magazine, Dear, Dave Magazine, Album Magazin and the catalog for Young Curators, New Ideas IV. Alper also curates an online site entitled The Archival Impulse, an archival project dedicated to his personal collection of vernacular photography.

www.benalper.com

www.anindexofwalking.com

www.thearchivalimpulse.tumblr.com

Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published on our previous platform, In the In-Between: Journal of Digital Imaging Artists.

___________________________

Stay connected with In the In-Between