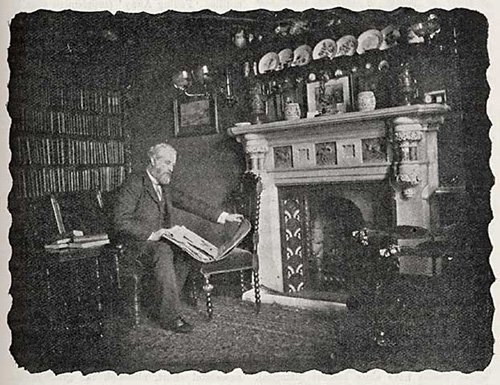

Self-Portrait, 1895.

Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published on our previous platform, In the In-Between: Journal of Digital Imaging Artists, and the formatting has not been optimized for the new website.

Henry Peach Robinson’s earliest endeavors at art were highly precocious oil paintings, one of which was accepted into a prestigious gallery showing while Robinson was only 22. Although he was already fully prepared for a lifelong career as a painter, Robinson was introduced to photography in the 1850s, and his initial fascination with the form quickly developed into a serious passion. The predominant culture of the Victorian era considered photography to be much more of a curiosity than an art form, a notion with which Robinson vigorously disagreed.

Robinson earned his fame with his combination printing, a photographic technique which he learned from his friend and contemporary Oscar Reijlander. An early form of photo-montage, the technique involved a very intricate process whereby several negatives were exposed onto the same paper. Although Reijlander pioneered the method, Robinson brought new levels of refinement to it, eventually producing prints composed of up to eight negatives. His work often imitates the genre paintings that were popular in England at the time, and the 1877 piece, When the Day’s Work is Done, is an excellent example of both his vision and technique.

________________________________________________

When the Day’s Work is Done, 1877.

________________________________________________________________________

In addition to his extensive photographic works, Robinson was actively involved in the era’s theoretical debates surrounding photography. Robinson even went so far as to claim that photography was an art form equal to the classical mediums of oil painting and sculpture. While this idea is widely accepted today, making such a claim was seen as eccentric at the time, and remained controversial well into the 1970’s. Robinson’s first and most famous book, Pictorial Effect In Photography: Being Hints On Composition And Chiaroscuro For Photographers, refined this argument in several ways, primarily by encouraging photographers to be just as consciously aware of composition, contrast, and color while framing and staging their image as a painter might be in constructing an image on canvas. The book’s title is also quite notably the first time the term “pictorial” is known to have been used in this way relative to photography, and is the basis for the term “pictorialism” as it has come to be defined today.

_______________________________

A Strange Fish, 1895.

______________________________________________________________________

While his aesthetic may strike a modern-day viewer as extremely conventional or even academic, Robinson was most well-known in his time for his nontraditional ideas, methods, and subject matter. Unlike most other photographers of the Victorian era, he was more than happy to stage his outdoor scenes inside of a studio, where he could completely control the lighting, the air flow, and the model. Indeed, rather than shooting “real” subjects in the field, he instead hired costumed actors or bored society ladies to pose for his photographs. Because his goal was ultimately to produce photographs that mimicked paintings, he had no qualms about mixing the real and the artificial in order to achieve a “pictorial” effect. One of his early pictorial works, Somebody’s Coming (1861), won a Silver Medal at the Photographic Society of Scotland’s 8th Annual Exhibition in 1864.

_____________________________

Somebody’s Coming, 1861.

____________________________________________________________

Robinson’s most famous piece, Fading Away (1858), depicts a young girl slowly dying while surrounded by her mourning family. Even though the scene was rendered quite sensitively, many critics felt that the subject was simply too private and delicate to explore through such a realistic and unforgiving medium as photography. This controversy, however, made him one of the most popular and recognized photographers in all of England. Much like Oscar Reijlander’s polemic allegory The Two Ways of Life, Robinson’s Fading Away was also purchased by Queen Victoria in the early 1860s, ultimately legitimizing both the photographers and the form. The fame that Robinson enjoyed as a result carried him throughout the rest of his career. Robinson’s art was featured in every exhibition held by the Photographic Society of London (later to be known as the Royal Photographic Society) for a period of more than thirty years.

______________________________________

Fading Away, 1858.

________________________________________________________________________

Robinson carried on creating composite prints until 1864, at age thirty-four, when the cumulative effect of years of poisonous darkroom chemicals brought on a serious decline in health. Although he had no choice but to give up his studio, he stayed active in the world of photographic theory, and continued to use the “cut-and-paste” method to create photo-montages. It was also during this time that he wrote Pictorial Effect In Photography, which remains an extremely relevant text to this day. By 1868 Robinson’s health had improved to a point where he felt able to open a new studio and begin composite printing again. In 1870 he was asked to take on the role of vice-president of the Royal Photographic Society, which he accepted, but resigned later as a result of disputes over aspects of photographic theory. He later joined a rival group calling itself the Linked Ring Society, and in 1900 was also elected an honorary member of the Royal Photographic Society. Soon afterward, Robinson succumbed to the toxic effects of the chemicals in his studio and died in early 1901.

____________________________________

What is it, 1895.

______________________________________________________________________

Robinson’s work can be viewed as anticipating the work of modern photographers, such as the arabesque theatricality seen in the works of of Philip-Lorca DeCorcia, or the extremely complex staging of Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson‘s tableaux. His insights and ideas regarding the evolution of photography were well before his time, exploring the furthest reaches of reality to where it extended into mystery and legend.

_______________________________

A Trespass Notice, 1880.

_______________________________________________________________________

In his final years, Robinson wrote the following passage, which predicted a sentiment that would surround the art of photography for decades to come:

“In the early days we were surprised and delighted with a photograph, as a photograph, just because we had not hitherto conceived possible any definition or finish that approached nature so closely… But soon we wanted something more. We got tired of the sameness of the exquisiteness of the photograph, and if it had nothing to say, if it was not a view, or a portrait of something or somebody, we cared less and less for it. Why? Because the photograph told us everything about the facts of nature and left out the mystery. Now, however hard-headed a man may be, he cannot stand too many facts; it is easy to get a surfeit of realities, and he wants a little mystification as a relief.”

____________________________________________________________________

Figures in Landscape, early 1890s.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

Robinson, Henry Peach: “Pictorial Effect In Photography: Being Hints On Composition And Chiaroscuro For Photographers.” Piper & Carter, 1869

Robinson, Henry Peach: “The Elements of a Pictorial Photograph”. Lund, 1896.

DeVries, David L., Rosen, Marvin J: “Photography & Digital Imaging, Revised Fifth Edition”. Kendall Hunt, 2002.

Images:

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=5451

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=5455

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=5445

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=5452

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=5446

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=34062

–http://www.photographymuseum.com/phofictionsmontages2.html

–http://www.museumsyndicate.com/item.php?item=34072

Text by Meghan Maloney

___________________________

Stay connected with In the In-Between