AK47

Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published on our previous platform, In the In-Between: Journal of Digital Imaging Artists, and the formatting has not been optimized for the new website.

Gregory Jones: First off Lewis, talk about what led to your interests in photography. Who or what were some of the influences that shaped your understanding of the medium?

Lewis Bush: There have been so many influences that it’s really hard to know where to start. The really big ones though have tended to be non-photographic. I grew up surrounded by art and artists and I think that had an enormous effect in exposing me to a plurality of artistic ideas and techniques. It also gave me quite a strong sense of the importance using your work to say something about the world. Later I studied history and that led to another way of viewing the world which was less about the surface (something photographers inevitably fixate on) and more about these invisible or very gradual processes beneath.

These things sound very different and almost incompatible with photography, but then when I later started to photograph regularly they became very useful. I found much of the dogma of photography and particularly documentary photography very tedious and irrational, and injecting ideas from other practices like history offered a way to negotiate them. Historians have been worrying about issues like representation for far longer than photographers, and the debates about it are inevitably more sophisticated as a result.

GJ: Can you elaborate on the dogmatic aspects of documentary photography you are rallying against? Are they ideas brought on by the practitioners themselves, or are they consequences of how the products of the documentary field are consumed?

LB: Dogmas like that the photograph is truth, that certain practices like manipulation erode that truth, and so on. It’s hard to generalize about the source of these things. Some I think reflect photographer’s own view of themselves, for example as crusading photojournalists seeking to right wrongs (often without considering the wrongs they might be propagating in the process). Others are questions of consumption, particularly who consumes photographs and why.

Others still are more deeply related to the history of photography and the place it holds in society. Technologies are never neutral, they are products of the eras and societies in which they emerged. Photography obviously emerged in a Europe that was obsessed with empiricism and the idea that what could be seen could be understood. I think we are gradually becoming more circumspect about that idea but it still remains a fundamental and not always helpful one in photography and journalism. Much is beyond seeing, and documentary photography often absolutely fails to show what it claims to.

M14

GJ: Going back to your point about historians’ concerns with representation, I would draw parallels between the rhetoric of documentary and the styles of realism that developed in the centuries before the Impressionists opened the doors to a more interpretive form of picture-making. I think it could be said that one role of the artist is to work as historian, to create works that mark interpretations of their respective current day events, or of their own personal histories. Can’t we view documentary photography as an extension of a broader history of pictorial realism, one that has always paralleled the development of spoken and written social history?

LB: You could definitely see the role of documentary in that sense, and many photographers I’ve spoken to have talked about documenting an event or issue as a historical record, particularly when the present seems to offer no solution to the issue that interests them. The only problem is the assumption made by many photographers that meaning remains constant and what we see today will be understood the same way tomorrow.

The past often speaks a different language to the present, and what seems like good history to one era can be perplexing, frustrating or problematic to another. Herodotus is often held up as the father of modern history, but his histories contain descriptions of sea monsters. This doesn’t change the usefulness of his accounts exactly, and arguably there are similar things at play in many ‘realist’ paintings. They often say as much or more about how the painter and his patrons saw the events of their time than they constitute any sort of objective ‘document’ of that time.

GJ: You stated in an earlier email exchange we had that you are, “… indirectly interested in the way photography works and works on us…” How does your recent project, Vietnam Deprimed, reflect this interest?

LB: Many people seem to imagine that when they look at a photograph it transmits some rather objective information to them and then that is the end of the exchange. What has always really interested me is the way that exchange shapes our encounters with subsequent photographs. We become trained to expect certain things from certain images, and to understand those images in certain ways. Our brains often follow the neural path of least resistance, and as photographers and viewers we get stuck into certain habits of making and viewing.

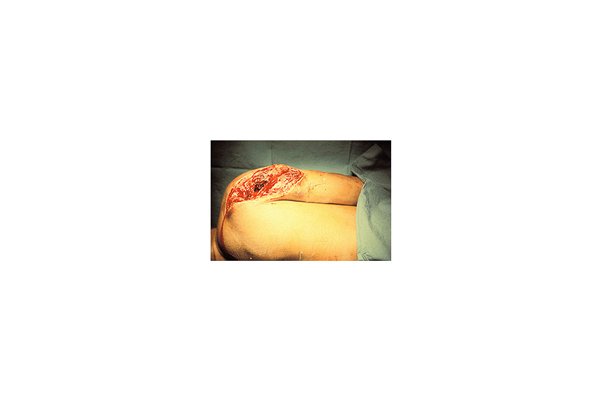

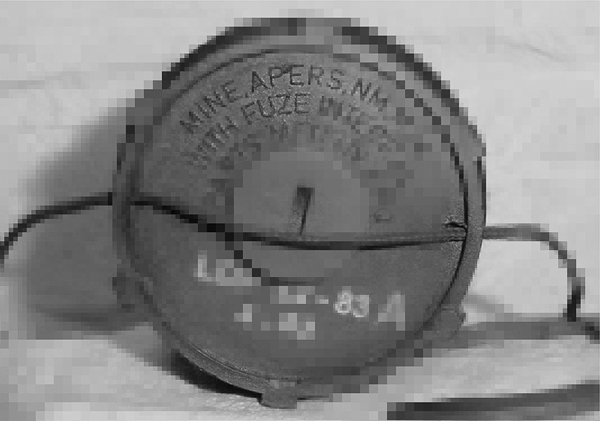

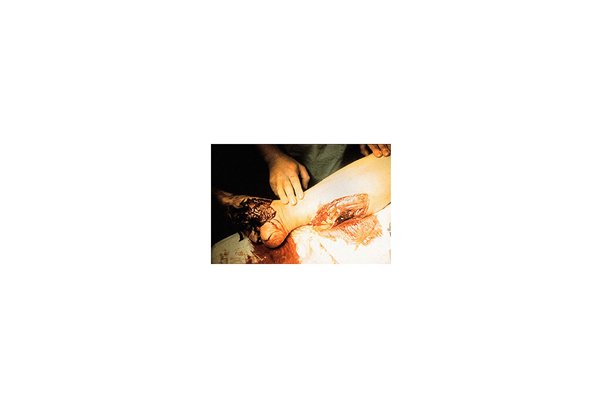

With Vietnam Deprimed I was really interested in trying to hijack some of these expectations about viewing and try to do something a little different. I’ve always been interested in juxtaposition and the way the meaning of photographs change depending on context, and here the idea was to put together two sets of images which would never normally be seen in the same context. Images of weapons, and images of the wounds those weapons cause.

M26

GJ: think this work as a whole, this incredibly concise, can you talk us through some of your thought processes when selecting and editing the images you used?

LB: As it often is, that was defined by the nature of the material. Trying to locate images of wounding with specific captioning about the cause was not an easy task, and as ever in these sorts of projects there is space for mistakes and uncertainty even in the final selection. Beyond the limits imposed by the sources I had available I was also unambiguously selecting the images I found most shocking because that shock element seemed important to the project. It’s also of course very problematic. If you look at anti-war photographic works [by photographers] like Ernst Friedrich and Krieg dem Krieg, [they] rely purely on shock value to warn against the horrors of war, they tend to be quite ineffective as propaganda devices. Visceral images shock us initially, but with repeated viewings they cease to become disturbing, which in itself is a disturbing thing.

GJ: One aspect to this work that I appreciate is the bluntness of it. The images of wounds were created in a very cold and straightforward fashion, and the pictures of the weapons that caused those wounds, though re-rendered through the pixelation, illustrate the subject matter clearly and to the point. I think the way you choose to present each style as a back-and forth aesthetic experience really leaves the viewer with no choice but to draw the connections of cause and effect. So I see a strong didactic aspect to this work, as if you intend to inform and teach the audience how images function. I often wonder about the responsibility that artists have in educating artists in visual literacy, is this a goal of yours?

LB: In terms of my personal work I don’t see it as my role to educate anyone, both because that rather patronizingly presupposes that people need educating. At least in terms of visual culture I think we’ve never seen such sophisticated understanding of the way images work amongst people, which I think is partly a consequence of our constant exposure to them and perhaps also the fact that so many of us now make and construct our own images as well as looking at them. Take a look at a teenager’s Instagram account and you often find a really sophisticated sense of image meaning and construction at work, even if the user can’t necessarily articulate what they’re doing in an academic way.

To see my role as teaching would also ignore that fact that all the information I gather is out there anyway, available to almost anyone to access and learn about themselves. Rather I think what I do is to take raw information that anyone can look at and learn about, and use it to construct an argument which is specific to where I stand in the world. Whether people agree with that argument or not is up to them. So in that sense I see my work as being maybe more dialectic than didactic.

B52

GJ: This series was created within the scope of a larger, multi-artist project entitled Media & Myth: Mass Media and the Vietnam War, for the London College of Communication’s NAM project. What were the origins and goals of this project?

LB: In the beginning was the NAM Project which was a multimedia research project within the London College of Communication. The project was intended to encourage post-graduate documentary photography students at the college to engage with the historic representation of conflict, in particular the Vietnam War. Vietnam Deprimed was my small contribution to that much larger research project.

Media & Myth in turn came later and was a collaboration between me and Monica Alcazar-Duarte, who had also studied documentary photography at London College of Communication. We both felt it was a shame that much of the work created for the NAM project had never been exhibited as a cohesive display. Our aim was to bring together some of the more visual research pieces and show them in a way which provoked some thought about how the Vietnam War was documented at the time, and how it has been commemorated since.

Alongside the student work on display we also negotiated permission to reproduce some materials from the Stanley Kubrick Archive, which is part of the University Special Collections housed at London College of Communication. We eventually selected a series of sketches from Kubrick’s 1987 Vietnam War film Full Metal Jacket which illustrate his plans to turn an old gas works in east London into a set for the war torn Vietnamese city of Hue. This seemed to us quite an apt analogy for some of the myth making that continues to surround the war.

GJ: Finally, what projects are you currently pursuing, and what are you looking forward to over the next year?

LB: I tend to work on several projects at the same time. At the moment I’m working on the sixth draft of a book called Numbers in the Dark which explores the world of ‘numbers stations’. These are covert radio stations operated by intelligence agencies and used to transmit coded messages to operatives in hostile countries. They originated during the Cold War but continue to broadcast today, and I’m interested in what they saw about the intersections between technology and surveillance, the past and the present, the secret and the public.

I’m also finalizing a revised edition of an earlier work called War Primer 3 which I hope to soon republish. As the name suggests this is in many ways a direct descendent of Vietnam Deprimed, employing some of the same visual strategies but in a very different setting. War Primer 3 uses appropriation to critique the exploitative behaviors endemic in the art world, but also to critique labour inequality more widely in the world.

Beyond that I have lots of plans for next year including new curatorial projects, lots of writing work, and starting to teach part-time on a regular basis from September. On top of all that I have a few ideas for new projects which will be hard to resist!

Installation of Media & Myth exhibition at FORMAT Festival, Derby. March 13th – April 13th, 2015.

______________

Bio:

Lewis Bush (London, 1988) studied history at the University of Warwick, and worked in public health before gaining a master’s degree in documentary photography from the London College of Communication. He has since gone on to teach photography there and at other institutions in the United Kingdom. At the same time he develops his own personal photography practice, and writes extensively on the medium’s history and its contemporary use for a wide range of print and online titles as well maintaining the Disphotic photography blog. He also curated occasional exhibitions and photographs for clients in the heritage, cultural and education sectors.

___________________________

Stay connected with In the In-Between