Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published on our previous platform, In the In-Between: Journal of Digital Imaging Artists, and the formatting has not been optimized for the new website.

The following round table interview is conducted by the artists included in the group exhibition Trompe L’oeil: The Constructed Image at Galerie Protege in New York City (June 8 – July 6, 2017).

The interview format allows for each artist to ask a question for the rest of the group to respond to.

Installation View. Courtesy Gallerie Protégé.

Introduction

How can we modernize the way we think about photography? Not just in the conversations surrounding digital vs. analog––old vs. new––but creating an improved taxonomy around processes and ideas that are universal to the medium and art making at large? A more holistic approach to an ever-changing landscape?

This connective tissue between ideas, intervention of the hand being central, is the basis of the group show, Trompe L’oeil, which features six artists constructing images. Brea Souders paints with photo chemistry, rephotographs, and disrupts the temporality as the chemicals chew through the layers of film. Sheida Soleimani strings narratives and sourced images from the internet, construction paper to create collage installations that are then captured. Within each intervention, new aspects of the evolving media and our relationship to it emerge. As a part of the show, I set out to generate a conversation between the artists about their practice. This is what they had to say:

–Danielle Ezzo, curator

——————————-

Danielle Ezzo: We all use the intersection of other media to make photographs that talk about the state of photography itself. How to you think this helps or hinders the contemporary state of image-making?

Anna Yeroshenko: I think it opens up new possibilities for the medium and expands the definition of photography whose purpose is no longer to describe an existing reality, but to create a new one.

Anastasia Somaylova: In our age of social media, photography became synonymous with living itself. We mostly take this democratic and accessible medium for granted, adding to the infinite pool of images daily. As artists who live most of their adult lives in the world so intensely saturated with images, it’s only natural for us to question the expected purpose of photographs; to provide a singular narrative or deliver some sort of meaning in a traditional way.

Brea Souders: I’m not especially focused on the state of photography in my work. People sometimes attach a related inquiry to my projects, but it’s not a subject I feel a need to reckon with. I believe photography is flourishing in all its forms right now. Photographs will continue to be potent and powerful. Even today as much as we discuss lies and over-saturation, we’re simultaneously affected daily by the images we see. I don’t think we need to obsess about it.

Charlie Rubin: I think using multiple media types is becoming a part of contemporary image-making. Taking a picture and hanging it on the wall is just not interesting to me anymore

Sheida Soleimani: This is so helpful in continuing to construct the dialogue around what a photograph actually is/can be. We have been conditioned to call an image ‘photographic’ for possessing certain qualities; oftentimes, we think of a photograph as an image that explores it’s surrounding world in a documentary or candid means. Through examining the notion of artifice, the creation of a photograph can adopt an interdisciplinary practice, and through constructing the subject of an image, we are able to mediate the idea of what exactly a photograph can be.

Danielle Ezzo: Agreed, it can only help. The vast majority of conversation around photography still tends to be centered around classic constructs and concerns. I’m interested in how the medium is developing and evolving, and how it informs everything that came before.

You Never Trusted Me, from the series Hidden Parts. Danielle Ezzo, 2017.

Charlie: Why/When did you start moving away from “straight photography” and toward altering images?

DE: I really never approached my artwork as straight photography. In the beginning, I felt like I had to take advantage of the tools that I had available because that’s what I had to work with, and through those trials found clever workarounds, often in Photoshop, to try and make better photos. This naturally led into the meta conversations about the process and distortion of the images that you see in my work today.

BS: In my very first photography class we were cutting our pictures into strips and weaving them together. But it was more process than promenade back then. Later on, I went through a period where I tried taking straight documentary photographs. In that time, I worked on several documentary and portrait projects. I felt a responsibility to at least try. It was an interesting experience, but it’s not what I’m made to do.

AS: Technically the images in my Landscape Sublime series are straight pictures. They might look like digital collages, but they are still photographs of three-dimensional tableaus that I construct out of paper prints. I wanted to create an illusion of digitally simulated space that can only be dispelled at the full scale of the final print, when you start seeing the imperfections like paper cuts and scratches on all those surfaces in the set.

AY: I’ve been always interested in creating illusions. I used to like to photograph at night––dusk alters the contours. It frees up space for imagination. In this regard, my constructed photographs are just one step further in an attempt to push the limits of perception.

SS: When I was 18, my dream was to be a Nat Geo photographer and to explore the world and take photos (total teenage pipe dream). On a trip to Puerto Rico with my parents, I wanted to photograph the people around me and noticed a man working at a fruit cart––it was raining, and I thought it looked like it would have been a great photograph. The instant I raised my camera and pointed it at him, I felt like an image of him taken by me would have been exploitative. Honestly, since then, I feel that most of photojournalism and photography is an exploitative act. For me, it comes down to intention, framing, and output and if I am exploiting my subject, how am I doing so, and what dialogue surrounds it? Through constructing images and scenes for the lens, I get to control exactly what I want to appear in the frame.

CR: I started moving away from straight photography around 2010. My images were beginning to lose meaning and I wanted to change that.

Sports Car. Charlie Rubin, 2017.

Sheida: What is your relationship to research both within your process & the final work?

DE: I find it grounding to approach my work from an empirical position. Holding myself to a hypothesis, doing research about process and concept, and making sure the work connects to that research, even if only in loose terms. The longer someone spends time with your work, the more they should be rewarded for looking, so I attempt to do this through embedded cues of visual culture as a way of getting in.

CR: My work is very intuitive, meaning research does not play a large role in my process. However I have researched, in general, art historical references and the other multimedia/ photographic artists that have come before me.

BS: I spend a good amount of time researching materials and chemistry. Outside of process, there is a wide range of things that I like to research, much of which funnels into my work eventually in one form or another.

AS: Photography is both the medium and the subject of my work. In Landscape Sublime I examine photographic typologies of the natural world as found in images shared on social media. I explore the ways in which these widely circulated and collectively repeated images create a perception of how specific landscapes should look like, a type of imaginative geographies.

AY: My work is about architecture just as much as it is about photography. So I find inspiration within the field of architecture whether regarding aesthetics-based issues, social concerns or philosophical reflections.

SS: All of my practice heavily relies on research––learning about the social and political histories of the places I am discussing in my works, to finding source materials and images to exist in my images. My practice would be non-existent without researching the background of the people, places, and politics of the spaces I create.

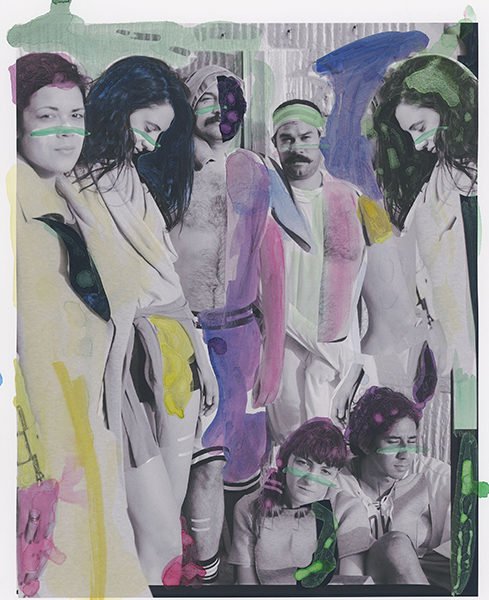

Filleting. Sheida Soleimani, 2015.

Brea: Outside of your conceptual framework, are there psychological underpinnings to your process? For instance, altering photographic material through cutting, collage/assemblage, paint overlay and digital retouching could stem from a range of internal desires – catharsis, an act of violence, ownership, control, physical connection, fantasy. Do these acts make you feel naughty, powerful, connected, free, etc?

SS: I think a lot about collage in my practice as an aggressive act––cutting the paper and ripping it, and reshaping it in a sense creates a cyborg. With much of the subject matter I use, the act of collage becomes a re-assertion of the violence that occurs in the source imagery.

DE: In The Intentional Object, there’s this idea of transformation. Both the image into something else, by way of digital manipulation; and the subject matter within the image. There’s a metanarrative there that by distorting the image I’m, in turn, reclaiming whatever fleeting moment was initially captured by the camera. Pinning down memory is slippery that way though, it never really wants to stay put, so there might be this feeling that something is always out of reach for me.

BS: The damning part is while you can’t escape yourself, you also can’t know yourself just by looking in a mirror. Even if you made the mirror. Likewise with my work, though there are tells and reveals, they have gone through their own transformation as they took shape. Which is to say yes, all of these ring true for me, but intertwined in such a way that the framework still unveils more truth than any psychological dive could.

CR: I definitely feel an internal desire to damage or change some of my images. This seems to be an attempt to create a fantasy or escape. And yes these acts make me feel free.

AS: For me, assembling the individual prints into a still life is a meditative process. When I started working on Landscape Sublime series in 2013 constructing sets out of paper was second nature to me since I came into photography from architecture and interior design. I used to make paper models of interiors and stage sets for projects at my Russian university for five years, so the act of building tabletop scale worlds transferred over into photography.

AY: I create new structures out of photographs of existing buildings with an intention to bring to the viewer the joy of looking at the things we are surrounded by and take for granted. By doing so I, perhaps, fulfill what I gave up doing as an architect. For me, it’s also a way to critique the dehumanizing nature of the architectural style prevailing on the outskirts of cities.

Still Rosie, from the series Hole in the Curtain. Brea Souders, 2015.

Anastasia: Do you think there are still rules and expectations about how photographic art has to be made? I find myself at a constant battle with dust, feeling the need to touch it up, yet questioning why I am still doing that; or in my recent collages, with the unevenness of the glued surfaces. Do you ever come across similar preconceptions while in the process of making your photographs?

BS: If there are still rules, let’s ignore them. Or better yet, banish them. Having learned photography in a traditional darkroom, I too obsess over dust and a certain definition of perfection. It’s one of those formative experiences that’s difficult to shake, and it does have its place depending on what you’re trying to do. I’m currently working on sculptural reliefs made with glass and have tried to resist thinking about them too photographically. I feel that urge, to “erase” glue marks, paint smudges and little imperfections in the glass. Not doing it under the shadow of compulsion is an instructive exercise in letting go. Especially for us, because I think it’s hard for photographers to relax. In my projects Film Electric and Hole in the Curtain, I decided to embrace imperfection and let go a bit – imperfection was an integral part of the works. Wabi Sabi.

DE: There’s an inherent neurosis with being a photographer. The math, the chemistry, the cleanliness.. there’s a precision to producing a photographic object, in the traditional sense of the word. I’m always trying to break free of that behavior, as I don’t think it’s always conducive to the ways of being an artist. I try to unencumber myself with varying levels of success.

CR: Yeah, I have similar battles––what does it mean to mount and frame a photo flat? what does it mean to put a matt on a photo? Why should I take dust off negatives? How large can I make something without losing its sharpness? I think these rules are becoming antiquated and we are trying to break out of them.

AY: The photographic industry is so broad today that I think it is the matter of finding your niche within it. There is certainly a standard or fashion for each category of photography. But I believe it is the work that does not fit in any of them makes the difference.

SS: No, I think to give oneself boundaries and rules becomes stifling, and makes us less able to change the dialogue surrounding what a ‘photograph’ actually is.

AS: I would say that there are certain aspects about my process that I still feel the need to justify. I’m often asked why I don’t use large format camera to photograph my sets to which I respond that my work is about the accessibility of images from social media sites, the communities that users create in order to view and comment on those images, the sharing aspect of pictures online. I opt for a democratic method of using a digital SLR, which is the technology that is used to create most of the images I use as a source material.

Mountain Peaks, from the series Landscape Sublime. Anastasia Samoylova, 2013.

Anna: In constructing an image what do you appreciate more – the control over the process or the spontaneity of the result?

SS: I’m a control freak that appreciates when I can make one spontaneous decision while making an image.

CR: A balance of spontaneity and subtlety is key for me.

AS: It is both for me too. It usually takes a few hours to build a set, yet the elements are never in a fully solidified state; it all can fall apart at any given moment. The trick is to press the shutter release when the composition feels resolved but not overdone.

BS: Neither takes primacy. In fact, they’d lose importance in the singularity of favored status. It’s the relationship between the two – the push and pull – that I’m interested in. The way I see it, I’m setting a stage. A specific environment. A place where things can unfold in unexpected ways. I do like the surprises, but of course I also like the control. Art making is most exciting to me when it mimics real life – when we try to exert control but end up being surprised. Over and over again. You have to continually keep up and react to the surprise. Therein lies the elegant tension of making this work.

DE: I like ferreting out all possible outcomes, sometimes it’s playful, sometimes it’s analytical. I want to fully understand what I’m doing, so I know how to push beyond it intentionally. Yet, despite that need for control, happy accidents happen and they can be better than anything that could have been planned for. Feeding that tension is a good thing.

AY: I usually have a clear idea about what the final work should look like; however, the resulting image never looks like I envisioned it. There are too many variables involved in the process, so the result is always surprising. I think it is the balance of construction and chance that I enjoy the most.

Untitled #2, from the series Hidden Dimensions. Anna Yeroshenko, 2016.

Installation View. Courtesy Gallerie Protégé.

Trompe L’eoil is on view at Galerie Protégé through July 6, 2017.

Galerie Protégé | 197 9th Ave, New York, NY 10011

————————————————–

Bios

Danielle Ezzo navigates the photographic medium with a discursive interest in the “edges” of photography and it’s relationship to the historical, technological and the ever-changing digital landscape and how it meets the human form. Her practice involves connecting the optical and conceptual relationships with each another by creating a new visual taxonomy for looking at the figure through a post-photographic lens. Her work has been written about in the BostonGlobe, Tate, BKN Magazine, and Lenscratch and exhibited internationally at such galleries as IRL Gallery, Dose Projects, A.C. Institute, Daniel Cooney Fine Art, The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, The Far Eastern Museum of Art. Danielle has lectured at the academic conference HISTART’14 (Istanbul), Carrot Creative, and IFP Media Center about new digital workflows, on a panel about the future of photography atEyebeam, and is published in The New Inquiry. Danielle is a MFA graduate of Lesley University College of Art & Design (LUCAD).

Charlie Rubin’s work is an exploration of the ordinary, with a twist, dissolving the line between artificial and real. He diligently captures intimate details of cultural cues by way of landscape, still life, portraiture, and various multimedia techniques. At its core, Rubin presents a visualization of a change in culture. Using intuition as a guide, photography, painting, sculpture and collage collide creating a kaleidoscope vision. In 2013, Rubin was awarded the Foam Talent Award (Amsterdam), and published a book titled Strange Paradise with Conveyor Arts shortly after, in 2014. Rubin recently had his first solo exhibition in 2015 with Kopeikin Gallery in Los Angeles. Residencies include Vermont Studio Center and the Wassaic Project. Charlie has also contributed commissioned work for The New Yorker, W Magazine, The Creators Project, Vice, and Hearst Magazines. He has works in the collections of the MoMA Library, Henry Art Museum (Seattle), and other private collections. Other endeavors include a collaborative publication called Yo-NewYork (yo-newyork.com) and a bring your own art show series in friends’ apartments called Neighboring Walls (neighboringwalls.com). He earned an MFA from Parsons the New School for Design (New York), and a BA at Haverford College (Pennsylvania). Rubin currently lives and works in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, New York City.

Anastasia Samoylova was born in Moscow, received an MA from Russian State University for the Humanities, and an MFA from Bradley University. She served as an assistant professor of photography at Illinois Central College and Bard College at Simon’s Rock. She is currently based in Miami, where she is an artist resident at the Fountahead studios. By utilizing tools and strategies related to digital media and commercial photography, her work interrogates notions of environmentalism, consumerism and the picturesque. Samoylova’s work participates in the landscape photography tradition while scrutinizing the consumable products it generates. Samoylova has exhibited internationally, including Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston, and Pingyao International Photography Festival in China. Her work is included in the collection at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago and ArtSlant Prize collection in Paris. In 2015 she was granted an artist residency at Latitude Chicago. Her work has been featured in the New Yorker and Foam magazine.

Sheida Soleimani is an Iranian-American artist, currently residing in Providence, Rhode Island. The daughter of political refugees that were persecuted by the Iranian government in the early 1980’s, Soleimani inserts her own critical perspectives on historical and contemporary socio- political occurrences in Iran. Her works meld sculpture, collage, and photography to create collisions in reference to Iranian politics throughout the past century. By focusing on media trends and the dissemination of societal occurrences through the news, source images from popular press and social media leaks are adapted to exist within alternate scenarios.

Brea Souders has exhibited internationally in galleries and arts institutions, including Bruce Silverstein Gallery, Abrons Arts Center and the Center for Photography at Woodstock in New York, as well as the Hyères International Festival of Photography & Fashion, France, the Singapore International Photography Festival and the Peel Art Gallery, Museum and Archives, Canada. She has received a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant, a fellowship and residency with the Millay Colony of the Arts and a Darkroom Residency with the Camera Club of New York. Souders’ work has been reviewed in the New Yorker, Artnews, LA Review of Books, New York Times T Magazine, and Elephant.

Anna Yeroshenko is a Russian photographer, currently living in Boston, USA. She had studied Architecture and Design before she became a photographer and received her BFA in Design of Architectural Environment from Pacific State University in 2008. For over 5 years she worked as an interior designer for architectural agencies and as an editorial photographer for russian magazines in her hometown, Khabarovsk. Anna’s interest in photography brought her to the US where she studied at the Lesley University College of Art and Design (the former Art Institute of Boston) and received her MFA in Photography in 2015. In the U.S. and abroad she is known for her dynamic ideas that challenge the art of photography and push the boundaries of the medium with unique techniques and original subject matter. Anna’s work have been exhibited at Perth Centre For Photography in Perth, Australia, the Mall Galleries, in London, UK, Langham Place, Hong Kong among others.

___________________________

Stay connected with In the In-Between